Artikelnummer

LXBOTWCMBVBM1951

Autor

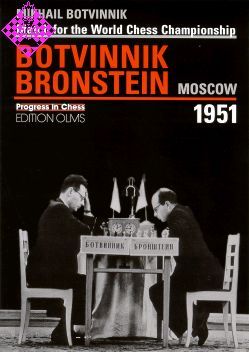

Botvinnik - Bronstein, Moscow 1951

Match for the World Chess Championship

128 Seiten, kartoniert, Olms

Aus der Reihe »Progress in Chess«

Final vergriffen

Three years after winning the World Championship, Mikhail Botvinnik had to defend his title against the challenge of David Bronstein. Though out of practice and largely outplayed by his brilliant young opponent, Botvinnik nevertheless demonstrated his fighting qualities, levelling the scores in the penultimate game and thereby retaining his title. All 24 games of the match are deeply annoted.

Preface

I consider the Botvinnik-Bronstein match for the world championship to be one of the most unusual. It has been insufficiently well studied, and little has been written about it. Meanwhile, it is rather interesting, in that it saw a meeting of two completely different opponents - in style and in their general approach to chess.

Bronstein, to all appearances, was an uncomfortable opponent for Botvinnik. David lonovich was a highly dynamic player and he felt very much at home in a tactical battle, when the pieces began to 'leap around the board'. And although Botvinnik's tactical vision was in full working order, things were difficult for him when he was not in his best form. And it was this that happened in the 1951 match, which therefore proved extremely difficult for Botvinnik.

I should like to point out certain features of this match. Firstly, its unfavourable outcome for White. Of the modern matches for the world championship, in this respect it is unique. I think that this is associated with the fact that for Bronstein, a player of practical, tactical inclination, the colour of the pieces was not of great importance. While Mikhail Moiseevich, if he went in for a complicated game with White, often allowed counterplay, after which Bronstein was no longer possible to stop. It is generally thought that Bronstein should have won the match, that he was simply unlucky, that he lacked a little something at the finish... I do not agree with this. After a careful study of the games, I have come to the conclusion that on the whole Botvinnik dominated. He played more strongly, even though he was in far from ideal form.

I would divide the match into three phases. For the first 5-6 games there was an equal struggle. Then, right up to the 17th game, there was clear domination by Botvinnik. During this stage of the match his superiority would have been more marked, had it not been for a certain lack of training and (or) Bronstein's enormous resourcefulness.

I should mention that, while Botvinnik's play was on the whole meritorious, he had some obvious lapses. To these I would assign the 11th game and the 17th, which became a turning point. Apparently for the 40-year-old Botvinnik it had already become hard to withstand the tension. In the 17th game he was simply unrecognisable - he played so sluggishly! Beginning from this point, Bronstein seized the initiative. In matches of this level there will always be a turning point. Perhaps Botvinnik was tired, but also Bronstein is not the sort of player who can be outplayed in every game! At the end of the match he played at least no worse, deservedly winning the 21st and 22nd games. It was perhaps only these two games that Bronstein conducted well from beginning to end. To judge by them, it all pointed to the fact that Bronstein would win the title, but then came the day of the 23rd game...

Perhaps it was a question of nerves, or perhaps something else, but Botvinnik managed to defeat his opponent. As befits a great player, at the decisive moment he composed himself and conducted the game well. Although at some point Bronstein was closer to a draw than Botvinnik was to a win, on the whole I would not call this defeat for Bronstein accidental.

In the final, 24th game Bronstein launched an attack, but straight away it did not work... Apparently it was hard for him to come to his senses after the 23rd game. And when he offered a draw he was already in a bad position.

I think that the final result was quite fair. Of the games typical of Botvinnik I would single out the 7th, won in good positional style, where Bronstein was deprived of the opportunity to create 'his' play. The game most typical of Bronstein was the 5th. Botvinnik handled the opening better, but then Black began skilful counterplay, which initially did not seem very significant. However, gradually it became stronger and stronger, and Bronstein's pieces 'began to jump'; to all appearances, Botvinnik became rattled,

ended up in time trouble, overlooked a tactical blow and lost. In general it turned out to be a rather curious, 'playing' match, where the opening was not of great importance. By the standard of play it was perhaps not a model world championship encounter, but it was nevertheless sufficiently interesting. The match with Bronstein was in the nature of a warning signal for Botvinnik. But apparently, partly because it all turned out well, he treated this type of player superficially and 9 years later he lost to Tal in very similar style. When Botvinnik encountered such Tal-Bronstein' play, he found it very difficult. But, I repeat, he was a great player and for the return match with Tal he was able to make thorough preparations.

Vladimir Kramnik, World Champion Moscow, June 2001

Preface

I consider the Botvinnik-Bronstein match for the world championship to be one of the most unusual. It has been insufficiently well studied, and little has been written about it. Meanwhile, it is rather interesting, in that it saw a meeting of two completely different opponents - in style and in their general approach to chess.

Bronstein, to all appearances, was an uncomfortable opponent for Botvinnik. David lonovich was a highly dynamic player and he felt very much at home in a tactical battle, when the pieces began to 'leap around the board'. And although Botvinnik's tactical vision was in full working order, things were difficult for him when he was not in his best form. And it was this that happened in the 1951 match, which therefore proved extremely difficult for Botvinnik.

I should like to point out certain features of this match. Firstly, its unfavourable outcome for White. Of the modern matches for the world championship, in this respect it is unique. I think that this is associated with the fact that for Bronstein, a player of practical, tactical inclination, the colour of the pieces was not of great importance. While Mikhail Moiseevich, if he went in for a complicated game with White, often allowed counterplay, after which Bronstein was no longer possible to stop. It is generally thought that Bronstein should have won the match, that he was simply unlucky, that he lacked a little something at the finish... I do not agree with this. After a careful study of the games, I have come to the conclusion that on the whole Botvinnik dominated. He played more strongly, even though he was in far from ideal form.

I would divide the match into three phases. For the first 5-6 games there was an equal struggle. Then, right up to the 17th game, there was clear domination by Botvinnik. During this stage of the match his superiority would have been more marked, had it not been for a certain lack of training and (or) Bronstein's enormous resourcefulness.

I should mention that, while Botvinnik's play was on the whole meritorious, he had some obvious lapses. To these I would assign the 11th game and the 17th, which became a turning point. Apparently for the 40-year-old Botvinnik it had already become hard to withstand the tension. In the 17th game he was simply unrecognisable - he played so sluggishly! Beginning from this point, Bronstein seized the initiative. In matches of this level there will always be a turning point. Perhaps Botvinnik was tired, but also Bronstein is not the sort of player who can be outplayed in every game! At the end of the match he played at least no worse, deservedly winning the 21st and 22nd games. It was perhaps only these two games that Bronstein conducted well from beginning to end. To judge by them, it all pointed to the fact that Bronstein would win the title, but then came the day of the 23rd game...

Perhaps it was a question of nerves, or perhaps something else, but Botvinnik managed to defeat his opponent. As befits a great player, at the decisive moment he composed himself and conducted the game well. Although at some point Bronstein was closer to a draw than Botvinnik was to a win, on the whole I would not call this defeat for Bronstein accidental.

In the final, 24th game Bronstein launched an attack, but straight away it did not work... Apparently it was hard for him to come to his senses after the 23rd game. And when he offered a draw he was already in a bad position.

I think that the final result was quite fair. Of the games typical of Botvinnik I would single out the 7th, won in good positional style, where Bronstein was deprived of the opportunity to create 'his' play. The game most typical of Bronstein was the 5th. Botvinnik handled the opening better, but then Black began skilful counterplay, which initially did not seem very significant. However, gradually it became stronger and stronger, and Bronstein's pieces 'began to jump'; to all appearances, Botvinnik became rattled,

ended up in time trouble, overlooked a tactical blow and lost. In general it turned out to be a rather curious, 'playing' match, where the opening was not of great importance. By the standard of play it was perhaps not a model world championship encounter, but it was nevertheless sufficiently interesting. The match with Bronstein was in the nature of a warning signal for Botvinnik. But apparently, partly because it all turned out well, he treated this type of player superficially and 9 years later he lost to Tal in very similar style. When Botvinnik encountered such Tal-Bronstein' play, he found it very difficult. But, I repeat, he was a great player and for the return match with Tal he was able to make thorough preparations.

Vladimir Kramnik, World Champion Moscow, June 2001

Three years after winning the World Championship, Mikhail Botvinnik had to defend his title against the challenge of David Bronstein. Though out of practice and largely outplayed by his brilliant young opponent, Botvinnik nevertheless demonstrated his fighting qualities, levelling the scores in the penultimate game and thereby retaining his title. All 24 games of the match are deeply annoted.

Preface

I consider the Botvinnik-Bronstein match for the world championship to be one of the most unusual. It has been insufficiently well studied, and little has been written about it. Meanwhile, it is rather interesting, in that it saw a meeting of two completely different opponents - in style and in their general approach to chess.

Bronstein, to all appearances, was an uncomfortable opponent for Botvinnik. David lonovich was a highly dynamic player and he felt very much at home in a tactical battle, when the pieces began to 'leap around the board'. And although Botvinnik's tactical vision was in full working order, things were difficult for him when he was not in his best form. And it was this that happened in the 1951 match, which therefore proved extremely difficult for Botvinnik.

I should like to point out certain features of this match. Firstly, its unfavourable outcome for White. Of the modern matches for the world championship, in this respect it is unique. I think that this is associated with the fact that for Bronstein, a player of practical, tactical inclination, the colour of the pieces was not of great importance. While Mikhail Moiseevich, if he went in for a complicated game with White, often allowed counterplay, after which Bronstein was no longer possible to stop. It is generally thought that Bronstein should have won the match, that he was simply unlucky, that he lacked a little something at the finish... I do not agree with this. After a careful study of the games, I have come to the conclusion that on the whole Botvinnik dominated. He played more strongly, even though he was in far from ideal form.

I would divide the match into three phases. For the first 5-6 games there was an equal struggle. Then, right up to the 17th game, there was clear domination by Botvinnik. During this stage of the match his superiority would have been more marked, had it not been for a certain lack of training and (or) Bronstein's enormous resourcefulness.

I should mention that, while Botvinnik's play was on the whole meritorious, he had some obvious lapses. To these I would assign the 11th game and the 17th, which became a turning point. Apparently for the 40-year-old Botvinnik it had already become hard to withstand the tension. In the 17th game he was simply unrecognisable - he played so sluggishly! Beginning from this point, Bronstein seized the initiative. In matches of this level there will always be a turning point. Perhaps Botvinnik was tired, but also Bronstein is not the sort of player who can be outplayed in every game! At the end of the match he played at least no worse, deservedly winning the 21st and 22nd games. It was perhaps only these two games that Bronstein conducted well from beginning to end. To judge by them, it all pointed to the fact that Bronstein would win the title, but then came the day of the 23rd game...

Perhaps it was a question of nerves, or perhaps something else, but Botvinnik managed to defeat his opponent. As befits a great player, at the decisive moment he composed himself and conducted the game well. Although at some point Bronstein was closer to a draw than Botvinnik was to a win, on the whole I would not call this defeat for Bronstein accidental.

In the final, 24th game Bronstein launched an attack, but straight away it did not work... Apparently it was hard for him to come to his senses after the 23rd game. And when he offered a draw he was already in a bad position.

I think that the final result was quite fair. Of the games typical of Botvinnik I would single out the 7th, won in good positional style, where Bronstein was deprived of the opportunity to create 'his' play. The game most typical of Bronstein was the 5th. Botvinnik handled the opening better, but then Black began skilful counterplay, which initially did not seem very significant. However, gradually it became stronger and stronger, and Bronstein's pieces 'began to jump'; to all appearances, Botvinnik became rattled,

ended up in time trouble, overlooked a tactical blow and lost. In general it turned out to be a rather curious, 'playing' match, where the opening was not of great importance. By the standard of play it was perhaps not a model world championship encounter, but it was nevertheless sufficiently interesting. The match with Bronstein was in the nature of a warning signal for Botvinnik. But apparently, partly because it all turned out well, he treated this type of player superficially and 9 years later he lost to Tal in very similar style. When Botvinnik encountered such Tal-Bronstein' play, he found it very difficult. But, I repeat, he was a great player and for the return match with Tal he was able to make thorough preparations.

Vladimir Kramnik, World Champion Moscow, June 2001

Preface

I consider the Botvinnik-Bronstein match for the world championship to be one of the most unusual. It has been insufficiently well studied, and little has been written about it. Meanwhile, it is rather interesting, in that it saw a meeting of two completely different opponents - in style and in their general approach to chess.

Bronstein, to all appearances, was an uncomfortable opponent for Botvinnik. David lonovich was a highly dynamic player and he felt very much at home in a tactical battle, when the pieces began to 'leap around the board'. And although Botvinnik's tactical vision was in full working order, things were difficult for him when he was not in his best form. And it was this that happened in the 1951 match, which therefore proved extremely difficult for Botvinnik.

I should like to point out certain features of this match. Firstly, its unfavourable outcome for White. Of the modern matches for the world championship, in this respect it is unique. I think that this is associated with the fact that for Bronstein, a player of practical, tactical inclination, the colour of the pieces was not of great importance. While Mikhail Moiseevich, if he went in for a complicated game with White, often allowed counterplay, after which Bronstein was no longer possible to stop. It is generally thought that Bronstein should have won the match, that he was simply unlucky, that he lacked a little something at the finish... I do not agree with this. After a careful study of the games, I have come to the conclusion that on the whole Botvinnik dominated. He played more strongly, even though he was in far from ideal form.

I would divide the match into three phases. For the first 5-6 games there was an equal struggle. Then, right up to the 17th game, there was clear domination by Botvinnik. During this stage of the match his superiority would have been more marked, had it not been for a certain lack of training and (or) Bronstein's enormous resourcefulness.

I should mention that, while Botvinnik's play was on the whole meritorious, he had some obvious lapses. To these I would assign the 11th game and the 17th, which became a turning point. Apparently for the 40-year-old Botvinnik it had already become hard to withstand the tension. In the 17th game he was simply unrecognisable - he played so sluggishly! Beginning from this point, Bronstein seized the initiative. In matches of this level there will always be a turning point. Perhaps Botvinnik was tired, but also Bronstein is not the sort of player who can be outplayed in every game! At the end of the match he played at least no worse, deservedly winning the 21st and 22nd games. It was perhaps only these two games that Bronstein conducted well from beginning to end. To judge by them, it all pointed to the fact that Bronstein would win the title, but then came the day of the 23rd game...

Perhaps it was a question of nerves, or perhaps something else, but Botvinnik managed to defeat his opponent. As befits a great player, at the decisive moment he composed himself and conducted the game well. Although at some point Bronstein was closer to a draw than Botvinnik was to a win, on the whole I would not call this defeat for Bronstein accidental.

In the final, 24th game Bronstein launched an attack, but straight away it did not work... Apparently it was hard for him to come to his senses after the 23rd game. And when he offered a draw he was already in a bad position.

I think that the final result was quite fair. Of the games typical of Botvinnik I would single out the 7th, won in good positional style, where Bronstein was deprived of the opportunity to create 'his' play. The game most typical of Bronstein was the 5th. Botvinnik handled the opening better, but then Black began skilful counterplay, which initially did not seem very significant. However, gradually it became stronger and stronger, and Bronstein's pieces 'began to jump'; to all appearances, Botvinnik became rattled,

ended up in time trouble, overlooked a tactical blow and lost. In general it turned out to be a rather curious, 'playing' match, where the opening was not of great importance. By the standard of play it was perhaps not a model world championship encounter, but it was nevertheless sufficiently interesting. The match with Bronstein was in the nature of a warning signal for Botvinnik. But apparently, partly because it all turned out well, he treated this type of player superficially and 9 years later he lost to Tal in very similar style. When Botvinnik encountered such Tal-Bronstein' play, he found it very difficult. But, I repeat, he was a great player and for the return match with Tal he was able to make thorough preparations.

Vladimir Kramnik, World Champion Moscow, June 2001

| EAN | 9783283004590 |

|---|---|

| Gewicht | 325 g |

| Hersteller | Olms |

| Breite | 16,9 cm |

| Höhe | 23,7 cm |

| Medium | Buch |

| Autor | Michail Botwinnik |

| Reihe | Progress in Chess |

| Sprache | Englisch |

| ISBN-10 | 3283004595 |

| Seiten | 128 |

| Einband | kartoniert |

007 Preface by Vladimir Kramnik

009 From the Editor

011 An Historic Match

013 D. Bronstein (an assessment)

015 Match table

016 Game 1 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

019 Game 2 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Grünfeld Defence)

024 Game 3 Botvinnik - Bronstein (French Defence)

027 Game 4 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

030 Game 5 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

033 Game 6 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Sicilian Defence)

037 Game 7 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

041 Game 8 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Queen's Gambit)

044 Game 9 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

047 Game 10 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

051 Game 11 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Queen's Indian Defence)

054 Game 12 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

056 Game 13 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

060 Game 14 Bronstein - Botvinnik (King's Indian Attack)

065 Game 15 Botvinnik - Bronstein (French Defence)

067 Game 16 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

071 Game 17 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

075 Game 18 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

079 Game 19 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Grünfeld Defence)

083 Game 20 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Reti Opening)

086 Game 21 Botvinnik- Bronstein (King's Indian Defence)

090 Game 22 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

094 Game 23 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Grünfeld Defence)

099 Game 24 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

103 Appendix (notes from Botvinnik's red notebook)

114 Opening preparation before the match

120 Summary of the match with Bronstein

123 Translator's Notes

009 From the Editor

011 An Historic Match

013 D. Bronstein (an assessment)

015 Match table

016 Game 1 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

019 Game 2 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Grünfeld Defence)

024 Game 3 Botvinnik - Bronstein (French Defence)

027 Game 4 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

030 Game 5 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

033 Game 6 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Sicilian Defence)

037 Game 7 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

041 Game 8 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Queen's Gambit)

044 Game 9 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Dutch Defence)

047 Game 10 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

051 Game 11 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Queen's Indian Defence)

054 Game 12 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

056 Game 13 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

060 Game 14 Bronstein - Botvinnik (King's Indian Attack)

065 Game 15 Botvinnik - Bronstein (French Defence)

067 Game 16 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

071 Game 17 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Nimzo-lndian Defence)

075 Game 18 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

079 Game 19 Botvinnik - Bronstein (Grünfeld Defence)

083 Game 20 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Reti Opening)

086 Game 21 Botvinnik- Bronstein (King's Indian Defence)

090 Game 22 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Dutch Defence)

094 Game 23 Botvinnik- Bronstein (Grünfeld Defence)

099 Game 24 Bronstein - Botvinnik (Slav Defence)

103 Appendix (notes from Botvinnik's red notebook)

114 Opening preparation before the match

120 Summary of the match with Bronstein

123 Translator's Notes

Wir sind in Moskau, im Frühjahr 1951.

Drei Jahre sind vergangen, seit Michail Botwinnik 1948 im fünfköpfigen FIDE-Turnier Den Haag/Moskau den WM-Titel erkämpfte, der nach Aljechins Tod vakant war. Drei Jahre hat Michail Moissejewitsch, der russische Elektroingenieur, nun kein Turnier mehr gespielt. Eigensinnig nahm er eine Auszeit vom Schach, schrieb seine Doktorarbeit über "Synchronmaschinen" zu Ende und heiratete eine Ballerina vom Bolschoj-Theater. Jetzt ist er ein guter Tänzer wird berichtet, und wenn er ins Theater geht, erheben sich die Zuschauer zu Ehren des Weltmeisters.

Schach ist nicht Botwinniks einziger Lebensinhalt, für ihn ist es auch weniger Spiel, mehr ein komplexer Kampf.

Und als Naturwissenschaftler definiert er Schach als „unscharfes Problem", vergleichbar der Leitung eines Betriebs. Solche Probleme seien näherungsweise lösbar - mit menschlicher Logik oder einem Großrechner. Der 27-jährige Herausforderer David Bronstein ist 13 Jahre jünger und von ganz anderer Denkart: kühn und unternehmungslustig, er experimentiert gern und mag verblüffende Züge, sein Schachstil erinnert an den jungen Keres. Wenn Botwinnik ein Wissenschaftler des Schach ist, dann sieht sich Bronstein als Künstler. Dazu mag passen, dass er manchmal eigenartig verträumt ist: In einer Partie gegen Bolelawski starrte er 50 Minuten aufs Brett - vor dem ersten Zug.

Botwinnik macht sich viel Gedanken und Notizen über seinen Gegner, seit sechs Monaten bereitet er sich planmäßig vor auf die erste Titelverteidigung, alles wird bedacht. In einem geheimen Testmatch gegen Ragosin bestand dessen Aufgabe vor allem darin, dem Altmeister Tabakqualm ins Gesicht zu blasen: Er will noch härter werden.

ln seinen Aufzeichnungen ermahnt er sich: „Nicht den Gegner ansehen!"

Botwinnik hat gern alles unter Kontrolle, er liebt die Perfektion. Streng gegen sich selbst und sein Umfeld, politisch ein überzeugter Stalin-Anhänger, glaubt er an Plan und Partei und strikte Regeln, auch fürs Alltägliche.

Das schlägt sich im Sportpensum nieder, im minutiösen Stundenplan und im Eröffnungsrepertoire, das exakt auf den Gegner und seine Schwächen abgestimmt wird. Aber Botwinnik ist vielschichtiger - seine 3-jährige Schachpause deutete es schon an. Er, ein prominentes Mitglied der KP, weigert sich 1953, den Offenen Brief aller GM gegen die „Ärzteverschwörung" zu unterzeichnen. Und 1976 widersetzt er sich der öffentlichen Verurteilung Kortschnois nach dessen Flucht (auch Spasski, Bronstein und Gulko unterschrieben nicht). So verhielt sich kein

angepasster Sowjetbürger. Auch nicht ins übliche Bild passt, was Herausgeber Igor Botwinnik im Vorwort aus MBs Tagebuch zitiert: Beim WM-Kampf klatschten die KGB-Offiziere in ihrer Loge immer dann laut, wenn Bronstein etwas opferte oder eroberte; offensichtlich hatte er ihre Sympathien, nicht Botwinnik.

Das rote Notizbuch

Über Bronstein und die anderen großen Meister führt der Doktor-Ingenieur kleine Dossiers, Stärken und Schwächen werden knapp registriert, mal trocken, mal zynisch - und ausgewertet.

Der Einblick in die sehr persönlichen Notizen ist das Neue an dieser Neuerscheinung.

Nach Vorworten von Kramnik („Ich denke, das Endresultat war ziemlich gerecht") und dem Herausgeber („er mochte das Match nicht") ist Botwinniks schachliches und psychologisches Urteil über Bronstein zu lesen, sogar dessen körperliche Fitness wird abgeschätzt: die größten schachlichen Schwächen seien geschlossene Stellungen, Stellungen ohne Initiative und die Zeitnot. Dann zieht der WM knapp seine Schlüsse für das bevorstehende Duell.

Der Anhang des Buches enthält auf 20 Seiten solche Auszüge aus dem geheimen „roten Notizbuch". Darunter ist die Analyse von sechs Turnieren, Spieler für Spieler, immer mit Bronstein im Visier: Was machte er in der Partie gegen Kotow, wie kam er mit Szabo zurecht? Hier Botwinniks Notiz zu Stahlberg -Bronstein, IZT Saltsjöbaden 1948:

Spielte Grünfeld wie Boleslawski, akkurat, Vereinfachung, akzeptierte Remis in überlegener Stellung im 21. Zug! Feigheit oder Müdigkeit?

Zur Eröffnungsvorbereitung auf das Match sind 6 Seiten abgedruckt, mit Varianten, knappen Bewertungen und Partiezitaten. Dann folgt Botwinniks kritische Nachbetrachtung zur WM, im Hinblick auf die gespielte Theorie und neue Entwicklungen seither, datiert auf Juli und Oktober 51.

Der Kampf

Als das Finale am 16. März 1951 endlich begann, hatte der Weltmeister unerwartet viel Probleme, er ließ die gewohnte Sicherheit vermissen, ihm fehlte Spielpraxis. Nach vier Remisen lag Bronstein vorn, ab Runde 7 der Weltmeister. Alles schien klar, da gewann der Herausforderer Runde 21 und 22 und ging 11,5:10,5 in Führung.

Jetzt reichte Bronstein ein Punkt aus den zwei verbleibenden Partien zum Titel, während Botwinnik 1,5 aus 2 holen musste, nur um auszugleichen. Und Botwinnik schaffte es! Er gewann Runde 23 und remisierte Nr. 24, der Kampf endete unentschieden 12 zu 12 (+5 -5 =14).

Danach waren beide erschöpft - in jeder Hinsicht. Botwinnik musste sich in den nächsten zwei Turnieren mit dem fünften und dem geteilten dritten Platz begnügen. Und Bronstein scheint die WM entscheidend mentale Kraft und Selbstvertrauen gekostet zu haben: Nie wieder spielte er um den Titel.

Die Kommentare

Das Buch erschien zuerst in Russland; Igor Botwinnik hat die Texte ausgewählt und zusammengestellt, vermutlich ist er ein Neffe des Weltmeisters. Jetzt übersetzte Ken Neat die russische Ausgabe ins Englische und fügte eine Liste mit ein paar schachlichen Korrekturen in den Anhang („Translator's Notes"). Solche Anmerkungen sollten nicht an das Buchende angehängt, sondern in die Kommentare eingearbeitet werden - immerhin dreht sich in dem Buch alles um nur 24 Partien. Der Leser darf erwarten, dass deren Analysen auf aktuellem Stand sind, nicht auf dem vor 50 Jahren. Der mögliche Einwand, der längst verstorbene Michail Botwinnik sei der Autor, das Buch stelle also Schachhistorie dar und keinen aktualisierten WM-Bericht, überzeugt nicht: Von den 24 Partien kommentierte er nur die Hälfte: alle Gewinnpartien, einige Remisen, keine der fünf Verlustpartien. Die anderen Kommentatoren sind Ev. Sweschnikow, S. Flohr, G. Löwenfisch, A. Lilienthal und P. Romanowski (die drei zuletzt Genannten starben vor mehr als 40 Jahren). Es würde die oft knappen Kommentare und Varianten der Meisnicht abwerten, wenn neue Erkenntnisse zu den kritischen Stellungen mit aufgenommen worden wären -im Gegenteil.

Betrachten wir die entscheidende Phase in der vielleicht wichtigsten Partie der ganzen WM: Es ist die vorletzte Runde (23), Botwinnik braucht den vollen Punkt, er überlegt seinen Abga(s. Dg.).

Während er 20 Minuten nachdachte, sah GM Salo Flohr, sein Sekundant und Kampfgefährte aus den 30er-Jahren, schnell das starke 42.Lb1! Gleich nach Abbruch der Partie wandte sich Flohr damit an Botwinnik und schwärmte von den Gewinnaussichten - der nickte nur und schickte ihn nachhause zum Analysieren. Flohr beschäftigte sich die ganze Nacht mit möglichen Abspielen. Am nächsten Morgen wollte er seine Erkenntnisse präsentieren, Botwinnik verwies ihn an seine Frau (die kaum mehr als die Schachregeln kannte). Erst im Spielsaal gestand er seinem Helfer: Er hat nicht 42.Lb1 abgegeben, sondern 42.Ld6. Salo Flohr brach in Tränen aus - dass Botwinnik dem eigenen Sekundanten so misstraute und eine Nacht lang die falsche Stellung analysieren ließ, war zuviel für ihn. (In den WM gegen Smyslow und Petrosjan verzichtete Botwinnik zeitweise ganz auf Sekundanten).

Im Buch natürlich kein Wort zur traurigen Episode mit Salo Flohr. Wer die wichtigen Partien und heiklen Momente der WM 1951 besser verstehen will, ist gut beraten, weitere Bücher neben das Brett zu legen, zum Beispiel Kasparows My Great Predecessors II (oder die dt. Ausgabe). Darin wird auf 24 Seiten über das Match berichtet, 7 Partien werden vorgestellt samt ausführlichen Zitaten von Botwinnik, Flohr und den anderen; hier kommt auch Bronstein zu Wort. Kasparow korrigiert und erweitert das Bekannte um neue Analysen in beträchtlicher Menge und Tiefe. (Was noch nicht der Weisheit letzter Schluss ist, wie jüngste Korrekturen und Ergänzungen auf GKs neuer Homepage zeigen).

Die vorliegende Edition betrachtet die WM 1951 streng aus dem Blickwinkel von Michail Botwinnik. Jeder Partie ist ein aufmunterndes Motto aus seinem Tagebuch vorangestellt, sozusagen der Tagesbefehl an sich selbst. Für Runde 22 lautet er sinngemäß: Mehr Druck, Aktivität und Klarheit! Auf geht's. Gelassenheit und Druck - das Vaterland ist in Gefahr!

Der verbale Tritt in den eigenen Hintern hat an dem Tag nicht geholfen, Botwinnik verlor.

Am Ende jeder Partie gibt es ein kleines Fazit, wieder übernommen aus dem Tagebuch; z. B. Partie 15 (remis):

Alles ging gut, aber das Königsmanöver war nicht recht durchdacht, zum Ende hin spielte ich wie ein Idiot.

Interessant ist auch, wie Botwinnik in seinen Notizen den Herausforderer sprachlich kleinkriegt: Bronsteins Meinung wird nicht erwähnt, weder zu einer Partie, noch zu einem Zug oder gar zum zweimonatigem Duell allgemein. Und in den Analysen über Bronstein reduziert er seinen Gegner bis zur Unperson: Entweder erwähnt er ihn nur indirekt, oder geschrumpft auf Br. Die anderen Spieler erscheinen mit Nachnamen.

Offene Fragen

Das Buch lässt viele Fragen offen: Wer ist Herausgeber Igor Botwinnik, in welcher Beziehung steht er zu Michail B.? Dass er ein Neffe sei, ist eine Vermutung nach Hinweisen im Internet; im Buch äußert er sich nicht. Wie kam er an die vertraulichen Notizen und nach welchen Kriterien wählte er aus und ließ weg? Warum ist nur die Hälfder Partien von MB kommentiert? - war er es doch, der die Meister aufforderte, ihre Analysen zu publizieren und sich der Kritik zu stellen. Vermisst werden auch Quellenangaben und eine Bibliographie.

Es bleibt zu wünschen, dass Igor Botwinnik (oder ein anderer) nachlegt und mehr aus der Hinterlassenschaft des dreimaligen Weltmeisters veröffentlicht. Michail Botwinnik gründete die „Sowjetische Schachschule", keiner vor ihm ging Schach so wissenschaftlich an. Er wird viel nachgedacht und aufgeschrieben haben.

Dr. Erik Rausch - Rochade Europa Nr. 10 Oktober 2004

Drei Jahre sind vergangen, seit Michail Botwinnik 1948 im fünfköpfigen FIDE-Turnier Den Haag/Moskau den WM-Titel erkämpfte, der nach Aljechins Tod vakant war. Drei Jahre hat Michail Moissejewitsch, der russische Elektroingenieur, nun kein Turnier mehr gespielt. Eigensinnig nahm er eine Auszeit vom Schach, schrieb seine Doktorarbeit über "Synchronmaschinen" zu Ende und heiratete eine Ballerina vom Bolschoj-Theater. Jetzt ist er ein guter Tänzer wird berichtet, und wenn er ins Theater geht, erheben sich die Zuschauer zu Ehren des Weltmeisters.

Schach ist nicht Botwinniks einziger Lebensinhalt, für ihn ist es auch weniger Spiel, mehr ein komplexer Kampf.

Und als Naturwissenschaftler definiert er Schach als „unscharfes Problem", vergleichbar der Leitung eines Betriebs. Solche Probleme seien näherungsweise lösbar - mit menschlicher Logik oder einem Großrechner. Der 27-jährige Herausforderer David Bronstein ist 13 Jahre jünger und von ganz anderer Denkart: kühn und unternehmungslustig, er experimentiert gern und mag verblüffende Züge, sein Schachstil erinnert an den jungen Keres. Wenn Botwinnik ein Wissenschaftler des Schach ist, dann sieht sich Bronstein als Künstler. Dazu mag passen, dass er manchmal eigenartig verträumt ist: In einer Partie gegen Bolelawski starrte er 50 Minuten aufs Brett - vor dem ersten Zug.

Botwinnik macht sich viel Gedanken und Notizen über seinen Gegner, seit sechs Monaten bereitet er sich planmäßig vor auf die erste Titelverteidigung, alles wird bedacht. In einem geheimen Testmatch gegen Ragosin bestand dessen Aufgabe vor allem darin, dem Altmeister Tabakqualm ins Gesicht zu blasen: Er will noch härter werden.

ln seinen Aufzeichnungen ermahnt er sich: „Nicht den Gegner ansehen!"

Botwinnik hat gern alles unter Kontrolle, er liebt die Perfektion. Streng gegen sich selbst und sein Umfeld, politisch ein überzeugter Stalin-Anhänger, glaubt er an Plan und Partei und strikte Regeln, auch fürs Alltägliche.

Das schlägt sich im Sportpensum nieder, im minutiösen Stundenplan und im Eröffnungsrepertoire, das exakt auf den Gegner und seine Schwächen abgestimmt wird. Aber Botwinnik ist vielschichtiger - seine 3-jährige Schachpause deutete es schon an. Er, ein prominentes Mitglied der KP, weigert sich 1953, den Offenen Brief aller GM gegen die „Ärzteverschwörung" zu unterzeichnen. Und 1976 widersetzt er sich der öffentlichen Verurteilung Kortschnois nach dessen Flucht (auch Spasski, Bronstein und Gulko unterschrieben nicht). So verhielt sich kein

angepasster Sowjetbürger. Auch nicht ins übliche Bild passt, was Herausgeber Igor Botwinnik im Vorwort aus MBs Tagebuch zitiert: Beim WM-Kampf klatschten die KGB-Offiziere in ihrer Loge immer dann laut, wenn Bronstein etwas opferte oder eroberte; offensichtlich hatte er ihre Sympathien, nicht Botwinnik.

Das rote Notizbuch

Über Bronstein und die anderen großen Meister führt der Doktor-Ingenieur kleine Dossiers, Stärken und Schwächen werden knapp registriert, mal trocken, mal zynisch - und ausgewertet.

Der Einblick in die sehr persönlichen Notizen ist das Neue an dieser Neuerscheinung.

Nach Vorworten von Kramnik („Ich denke, das Endresultat war ziemlich gerecht") und dem Herausgeber („er mochte das Match nicht") ist Botwinniks schachliches und psychologisches Urteil über Bronstein zu lesen, sogar dessen körperliche Fitness wird abgeschätzt: die größten schachlichen Schwächen seien geschlossene Stellungen, Stellungen ohne Initiative und die Zeitnot. Dann zieht der WM knapp seine Schlüsse für das bevorstehende Duell.

Der Anhang des Buches enthält auf 20 Seiten solche Auszüge aus dem geheimen „roten Notizbuch". Darunter ist die Analyse von sechs Turnieren, Spieler für Spieler, immer mit Bronstein im Visier: Was machte er in der Partie gegen Kotow, wie kam er mit Szabo zurecht? Hier Botwinniks Notiz zu Stahlberg -Bronstein, IZT Saltsjöbaden 1948:

Spielte Grünfeld wie Boleslawski, akkurat, Vereinfachung, akzeptierte Remis in überlegener Stellung im 21. Zug! Feigheit oder Müdigkeit?

Zur Eröffnungsvorbereitung auf das Match sind 6 Seiten abgedruckt, mit Varianten, knappen Bewertungen und Partiezitaten. Dann folgt Botwinniks kritische Nachbetrachtung zur WM, im Hinblick auf die gespielte Theorie und neue Entwicklungen seither, datiert auf Juli und Oktober 51.

Der Kampf

Als das Finale am 16. März 1951 endlich begann, hatte der Weltmeister unerwartet viel Probleme, er ließ die gewohnte Sicherheit vermissen, ihm fehlte Spielpraxis. Nach vier Remisen lag Bronstein vorn, ab Runde 7 der Weltmeister. Alles schien klar, da gewann der Herausforderer Runde 21 und 22 und ging 11,5:10,5 in Führung.

Jetzt reichte Bronstein ein Punkt aus den zwei verbleibenden Partien zum Titel, während Botwinnik 1,5 aus 2 holen musste, nur um auszugleichen. Und Botwinnik schaffte es! Er gewann Runde 23 und remisierte Nr. 24, der Kampf endete unentschieden 12 zu 12 (+5 -5 =14).

Danach waren beide erschöpft - in jeder Hinsicht. Botwinnik musste sich in den nächsten zwei Turnieren mit dem fünften und dem geteilten dritten Platz begnügen. Und Bronstein scheint die WM entscheidend mentale Kraft und Selbstvertrauen gekostet zu haben: Nie wieder spielte er um den Titel.

Die Kommentare

Das Buch erschien zuerst in Russland; Igor Botwinnik hat die Texte ausgewählt und zusammengestellt, vermutlich ist er ein Neffe des Weltmeisters. Jetzt übersetzte Ken Neat die russische Ausgabe ins Englische und fügte eine Liste mit ein paar schachlichen Korrekturen in den Anhang („Translator's Notes"). Solche Anmerkungen sollten nicht an das Buchende angehängt, sondern in die Kommentare eingearbeitet werden - immerhin dreht sich in dem Buch alles um nur 24 Partien. Der Leser darf erwarten, dass deren Analysen auf aktuellem Stand sind, nicht auf dem vor 50 Jahren. Der mögliche Einwand, der längst verstorbene Michail Botwinnik sei der Autor, das Buch stelle also Schachhistorie dar und keinen aktualisierten WM-Bericht, überzeugt nicht: Von den 24 Partien kommentierte er nur die Hälfte: alle Gewinnpartien, einige Remisen, keine der fünf Verlustpartien. Die anderen Kommentatoren sind Ev. Sweschnikow, S. Flohr, G. Löwenfisch, A. Lilienthal und P. Romanowski (die drei zuletzt Genannten starben vor mehr als 40 Jahren). Es würde die oft knappen Kommentare und Varianten der Meisnicht abwerten, wenn neue Erkenntnisse zu den kritischen Stellungen mit aufgenommen worden wären -im Gegenteil.

Betrachten wir die entscheidende Phase in der vielleicht wichtigsten Partie der ganzen WM: Es ist die vorletzte Runde (23), Botwinnik braucht den vollen Punkt, er überlegt seinen Abga(s. Dg.).

Während er 20 Minuten nachdachte, sah GM Salo Flohr, sein Sekundant und Kampfgefährte aus den 30er-Jahren, schnell das starke 42.Lb1! Gleich nach Abbruch der Partie wandte sich Flohr damit an Botwinnik und schwärmte von den Gewinnaussichten - der nickte nur und schickte ihn nachhause zum Analysieren. Flohr beschäftigte sich die ganze Nacht mit möglichen Abspielen. Am nächsten Morgen wollte er seine Erkenntnisse präsentieren, Botwinnik verwies ihn an seine Frau (die kaum mehr als die Schachregeln kannte). Erst im Spielsaal gestand er seinem Helfer: Er hat nicht 42.Lb1 abgegeben, sondern 42.Ld6. Salo Flohr brach in Tränen aus - dass Botwinnik dem eigenen Sekundanten so misstraute und eine Nacht lang die falsche Stellung analysieren ließ, war zuviel für ihn. (In den WM gegen Smyslow und Petrosjan verzichtete Botwinnik zeitweise ganz auf Sekundanten).

Im Buch natürlich kein Wort zur traurigen Episode mit Salo Flohr. Wer die wichtigen Partien und heiklen Momente der WM 1951 besser verstehen will, ist gut beraten, weitere Bücher neben das Brett zu legen, zum Beispiel Kasparows My Great Predecessors II (oder die dt. Ausgabe). Darin wird auf 24 Seiten über das Match berichtet, 7 Partien werden vorgestellt samt ausführlichen Zitaten von Botwinnik, Flohr und den anderen; hier kommt auch Bronstein zu Wort. Kasparow korrigiert und erweitert das Bekannte um neue Analysen in beträchtlicher Menge und Tiefe. (Was noch nicht der Weisheit letzter Schluss ist, wie jüngste Korrekturen und Ergänzungen auf GKs neuer Homepage zeigen).

Die vorliegende Edition betrachtet die WM 1951 streng aus dem Blickwinkel von Michail Botwinnik. Jeder Partie ist ein aufmunterndes Motto aus seinem Tagebuch vorangestellt, sozusagen der Tagesbefehl an sich selbst. Für Runde 22 lautet er sinngemäß: Mehr Druck, Aktivität und Klarheit! Auf geht's. Gelassenheit und Druck - das Vaterland ist in Gefahr!

Der verbale Tritt in den eigenen Hintern hat an dem Tag nicht geholfen, Botwinnik verlor.

Am Ende jeder Partie gibt es ein kleines Fazit, wieder übernommen aus dem Tagebuch; z. B. Partie 15 (remis):

Alles ging gut, aber das Königsmanöver war nicht recht durchdacht, zum Ende hin spielte ich wie ein Idiot.

Interessant ist auch, wie Botwinnik in seinen Notizen den Herausforderer sprachlich kleinkriegt: Bronsteins Meinung wird nicht erwähnt, weder zu einer Partie, noch zu einem Zug oder gar zum zweimonatigem Duell allgemein. Und in den Analysen über Bronstein reduziert er seinen Gegner bis zur Unperson: Entweder erwähnt er ihn nur indirekt, oder geschrumpft auf Br. Die anderen Spieler erscheinen mit Nachnamen.

Offene Fragen

Das Buch lässt viele Fragen offen: Wer ist Herausgeber Igor Botwinnik, in welcher Beziehung steht er zu Michail B.? Dass er ein Neffe sei, ist eine Vermutung nach Hinweisen im Internet; im Buch äußert er sich nicht. Wie kam er an die vertraulichen Notizen und nach welchen Kriterien wählte er aus und ließ weg? Warum ist nur die Hälfder Partien von MB kommentiert? - war er es doch, der die Meister aufforderte, ihre Analysen zu publizieren und sich der Kritik zu stellen. Vermisst werden auch Quellenangaben und eine Bibliographie.

Es bleibt zu wünschen, dass Igor Botwinnik (oder ein anderer) nachlegt und mehr aus der Hinterlassenschaft des dreimaligen Weltmeisters veröffentlicht. Michail Botwinnik gründete die „Sowjetische Schachschule", keiner vor ihm ging Schach so wissenschaftlich an. Er wird viel nachgedacht und aufgeschrieben haben.

Dr. Erik Rausch - Rochade Europa Nr. 10 Oktober 2004