Artikelnummer

LXPISSNK

Autor

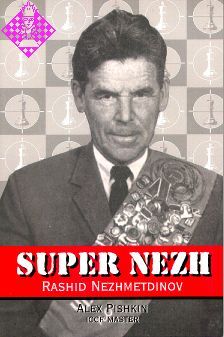

Super Nezh

Rashid Nezhmetdinov

221 Seiten, kartoniert, Thinkers' Press, 2001

Final vergriffen

Jvashid Neznmetdinov was unlike most chess players. Draws were almost an accident, or at the very least, a necessary evil to prevent losing a game which had gone awry. Raised in austere circumstances and learning to play checkers as well as he played chess, he became the Russian chess champion five times. His method was: ATTACK... ATTACK... ATTACK. His Tartar ferocity became legendary. World champion Mikhail Tal had become his victim so many times that Nezh became one of his trainers!

Nezh was more than a giant killer, he produced some games of genius-like creativity, such as the one against Polugaevsky in 1958. He could deliberate for the longest periods of time, over a game which appeared lost, only to finally reveal what he knew all along, that the game was his.

Besides his incessant ability to make deep combinations, he was also a purveyor of opening novelties, the best known being his 1954 origination of the Poisoned Pawn line in the Najdorf Sicilian (used later with great success by World Champion Bobby Fischer). His chess (being a 1. e4 player) embodied the Ruy Lopez, the Sicilian Defense, and the King's Indian Defense.

Nezh was more than a giant killer, he produced some games of genius-like creativity, such as the one against Polugaevsky in 1958. He could deliberate for the longest periods of time, over a game which appeared lost, only to finally reveal what he knew all along, that the game was his.

Besides his incessant ability to make deep combinations, he was also a purveyor of opening novelties, the best known being his 1954 origination of the Poisoned Pawn line in the Najdorf Sicilian (used later with great success by World Champion Bobby Fischer). His chess (being a 1. e4 player) embodied the Ruy Lopez, the Sicilian Defense, and the King's Indian Defense.

Jvashid Neznmetdinov was unlike most chess players. Draws were almost an accident, or at the very least, a necessary evil to prevent losing a game which had gone awry. Raised in austere circumstances and learning to play checkers as well as he played chess, he became the Russian chess champion five times. His method was: ATTACK... ATTACK... ATTACK. His Tartar ferocity became legendary. World champion Mikhail Tal had become his victim so many times that Nezh became one of his trainers!

Nezh was more than a giant killer, he produced some games of genius-like creativity, such as the one against Polugaevsky in 1958. He could deliberate for the longest periods of time, over a game which appeared lost, only to finally reveal what he knew all along, that the game was his.

Besides his incessant ability to make deep combinations, he was also a purveyor of opening novelties, the best known being his 1954 origination of the Poisoned Pawn line in the Najdorf Sicilian (used later with great success by World Champion Bobby Fischer). His chess (being a 1. e4 player) embodied the Ruy Lopez, the Sicilian Defense, and the King's Indian Defense.

Nezh was more than a giant killer, he produced some games of genius-like creativity, such as the one against Polugaevsky in 1958. He could deliberate for the longest periods of time, over a game which appeared lost, only to finally reveal what he knew all along, that the game was his.

Besides his incessant ability to make deep combinations, he was also a purveyor of opening novelties, the best known being his 1954 origination of the Poisoned Pawn line in the Najdorf Sicilian (used later with great success by World Champion Bobby Fischer). His chess (being a 1. e4 player) embodied the Ruy Lopez, the Sicilian Defense, and the King's Indian Defense.

| EAN | 0938650912 |

|---|---|

| Gewicht | 320 g |

| Hersteller | Thinkers' Press |

| Breite | 15,2 cm |

| Höhe | 22,8 cm |

| Medium | Buch |

| Erscheinungsjahr | 2001 |

| Autor | Alex Pishkin |

| Sprache | Englisch |

| ISBN-10 | 0938650912 |

| Seiten | 221 |

| Einband | kartoniert |

| Name | Thinkers' Press |

|---|

iv Explanation of Symbols

v Preface by Alex Pishkin

x An Appreciation by IM Rashid Ziyatdinov

xv Publisher's Foreword

017 1 Biography

033 2 Masterpieces

063 3 The Fight

091 4 Attack

123 5 Defense and Counterattack

141 6 Strategy

153 7 Opening Novelties

171 8 The Endgame

191 9 Small Raisins

206 Opponents

209 Openings' Index

211 Main Tournament and Match Results

214 Bibliography and Databases

215 Colophon

v Preface by Alex Pishkin

x An Appreciation by IM Rashid Ziyatdinov

xv Publisher's Foreword

017 1 Biography

033 2 Masterpieces

063 3 The Fight

091 4 Attack

123 5 Defense and Counterattack

141 6 Strategy

153 7 Opening Novelties

171 8 The Endgame

191 9 Small Raisins

206 Opponents

209 Openings' Index

211 Main Tournament and Match Results

214 Bibliography and Databases

215 Colophon

The world of chess is multifaceted. Yet, of all its sides, three are considered the most important: sport, science, and art. It is impossible to achieve complete success by developing your mastery in only one of these areas. Any outstanding master combines in himself these three sides to this or that extent. Happy are those in whom they have been harmoniously developed: Fischer, Spassky, and Kasparov.

Lasker and Petrosian were outstanding sportsmen, and from the present- Karpov. Steinitz, Euwe, and Botvinnik were distinguished by their scientific approach.

Alekhine and Tal can be called brilliant high priests of chess art.

It goes without saying that these champions were blessed by additional chess qualities as well, otherwise the list of champions would be different.

There are masters in whom certain chess qualities are developed to such a phenomenal extent that few of the recognised geniuses of chess can challenge them.

Are there many among the greatest who can compete in the theory of the endgame with Yuri Averbakh, Nikolai Grigoriev or Andre Cheron? Perhaps, only Smyslov and Rubinstein.

Are there many among the greatest who might surpass in the field of analysis Isaac Boleslavsky, Igor Zaitsev or Mark Dvoretsky?

But chess theory and analysis are still the applied side of chess. They are certainly necessary for a chessplayer, no less than the mastery of versification is necessary for a poet, and solfeggio, for a musician. What we value most of all in the poet and musician is the gift of creativity, that intangible, ephemeral thing which is called "a God's spark."

Among those who were endowed with "the God spark," and created many unforgettable masterpieces (though they never became world champions) were: Chigorin, Reti, Bronstein, Larsen, Ljubojevich ... To this list we should undoubtedly add Spielmann, Simagin, Tolush, Kupreichik and especially Nezhmetdinov.

The name of Rashid Gibyatovich Nezhmetdinov is not as well known to the western lover of chess. Indeed he is not included among "the greatest" of the chess world. He wasn't a grandmaster, though in the former Soviet Union one can count about two hundred owners of this title.

He wasn't famous in the international arena, simply because he had few chances to play outside of his own country.

Still, if you ask any chess master, no not even that, if you ask any man who likes art in chess and has become acquainted with the creative heritage of the chess masters of the past, he will surely say, "Ah, he is that master who regularly defeated Tal and who attacked so beautifully!" And that is true.

Despite his lack of the grandmaster title, Rashid Nezhmetdinov was a unique personality in the chess world.

In the USSR and, quite possibly, in the whole world, he was the only "master squared," that is, he was a chess master and a checkers master at the same time. Once Mikhail Tal jokingly called chess "algebra" and checkers "arithmetic." He hinted at a certain second-rate quality of a checkers game in comparision with a chess game, a game which many consider the "royal game." After Nezhmetdinov had finally given up checkers, he noted one time that all checkers contests can be reduced to Rook endgames. On the other hand, checkers players have often commented on the depth of calculations of variations in their favorite game, and especially its oriental varieties, like the Japanese "Go," as surpassing chess. We won't argue about this; these arguments increase the significance of Nezhmetdinov's double mastery of both games.

His talent fully blossomed and revealed itself when he was no longer young. He was 37 when he received the title of chess master. At that age, and even at a younger age, many famous chess masters disappeared from the scene (remember Fischer, Morphy, Pillsbury, Mecking... ?).

Nezhmetdinov gained his best results after 40. He made his debut in the USSR chess championship at 41, and the last time he became the Russian champion was at the age of 45. The last time he played in the finals of the all-Union championship was when he was almost 55!

In chess history you will seldom find similar cases of a chess player going on the "big stage" at such an "elderly" age. Some might remember Georg Salwe, the Russian champion of 1905, who also became a master after the age of 40. Contemporary chess practice shows that chess champions "are younger and younger," and that a chess player reaches his peak by the age of 25-30, and after 35, his sporting form slowly decreases. At that age, the ability to accurately calculate variations lessens. The ability to endure many hours of intensive mental exercise also declines, something which a chess master seriously needs. If this is true, and we cannot doubt the truthfulness of the conclusions of specialists, then how can we account for the phenomenal chess of Nezhmetdinov? This is even more remarkable if we take into consideration that his style of playing chess was primarily based on the increase of tension on the chessboard and the extremely intensive calculation of variations.

It is impossible to explain this, just as it is impossible to answer the question "How can one become a genius?"

Rashid Nezhmetdinov holds an unequaled record: he was chess champion of Russia five times. All in all, he played in the finals of the Russian championships 16 times.

Besides those five first places, another five times he was among the prize-

winners. Here also should be added a silver medal in one, the checkers championship. His closest rival among Russian chess champions is the great Chigorin, who won three championships at the beginning of the century.

His chess talent was unique. Lev Polugaevsky called him "the greatest master of the initiative."

M. Tal says: "His games reveal the beauty of chess and make you love in chess not so much the points and high placings, but the wonderful harmony and elegance of this particular world." Tal was a good friend and admirer of Nezhmetdinov's creative activity. In the preface to Nezhmetdinov's book Selected Games he wrote: "In Nezhmetdinov, more than in anybody else, you can see the difference between his creative and sporting achievements."

When a game was dry and there was much maneuvering, he got bored and sometimes played negligently. As a result, he lost more often than was expected. There were tournaments in which he never experienced a feeling of inspiration and creative enthusiasm. He didn't win laurels in those events.

On the other hand, when he managed to achieve a position that aroused the desire to create, when he succeeded in luring his opponent onto the slippery ice of combinational complications, when he obtained the initiative, then he was fearsome and irrepressible. It didn't matter then who was facing him across the board.

Rashid Nezhmetdinov's talent resembles a tree that, by some miracle, has grown on a bare cliff. He had a difficult childhood and was a youth of hunger. During his best years for chess he was in the army, and then came the

war. He gained access to serious chess competitions only when he was 35. It was much later when young talents in the Soviet Union could achieve wonderful conditions for growth and blossoming. They had experienced teachers in the Pioneer palaces, regular training meetings during school vacations, Chess Informants, and computers.

Rashid had no dreams of anything like that. Practically speaking, he alone created the brilliant chess master Nezhmetdinov. This might explain why Nezhmetdinov was not only a master, but also a brilliant coach who trained many masters and gave many young people their access to chess.

I hope this book will broaden the circle of admirers for the creative abilities of this wonderful chess player and perhaps arouse in some ambitious young man an aspiration to achieve something in the cruel and beautiful world of chess. Perhaps, another Super Nezh.

Personal Thoughts for the Westerner

I have never been Rashid Nezhmetdinov's pupil or friend. I met him only twice at team championships, but not at the chessboard.

In the 50s when I was making my first steps in chess, Nezhmetdinov's games appeared quite often on the pages of chess magazines. It so happened that it was through his creative play that I began to comprehend the beauty and depth of chess. Since that time I have always remained an unfailing admirer of his wonderful talent.

Unlike many other great Soviet masters, Nezhmetdinov enjoyed the respect of his contemporaries, and many of his games have become known to thousands of chess lovers; some very famous grandmasters cannot boast that. During his lifetime he had a book published about his life in chess (Kazan, 1960). The book was published by the provincial publishing house and the circulation was small. Unfortunately, not all of his best games were included. As for the second edition of that book, which was considerably expanded, Nezhmetdinov never saw it for he had passed away. It was republished in 1978, and this printing was larger, 50,000 copies.

Later J. Damsky authored an excellent book in 1987 to commemorate Nezhmetdinov's 75th birthday. Rashid Nezhmetdinov was published in an edition of 100,000 copies where Nezh is presented not only as a bright chess master, but also as a self-made man who devoted his life to chess, enduring many difficulties along the way.

Before I decided to write one more book about Rashid Nezhmetdinov, I studied thoroughly all that had been published, and primarily his games and commentaries on them. Nezhmetdinov's own notes are characterized by a laconic, terse style, and concrete analysis. My task was to remove some analytical inaccuracies and some very rare mistakes, as well as to refresh his opening theories.

Damsky's commentaries on some games are also good, especially if he himself witnessed those games or saw them demonstrated by Rashid. Unfortunately, Damsky's commentaries on some games are too curt and fail to fully reveal the depth of their contents. There are some analytical mistakes as well in Damsky's book. Some of Nezhmetdinov's brilliant games didn't get into Damsky's book or were only given as fragments.

In the end I came to the conclusion that it would be necessary to reselect

the games and to comment on them all over again.

I tried to use Nezhmetdinov's original analyses on those parts of the games that required detailed analysis. I also used his brilliant evaluations of positions which disclosed the real situation with utmost clarity and in few words. In these cases Nezhmetdinov's notes were quoted.

The selection of games has been changed according to their composition, as well as order of their arrangement. I have rejected the common method of chronological order in arranging the games. This approach to chess art is a good one for those great men of the chess world whose creative work is many-sided, and whose mastery is universal. The average level of games of those type of masters is high. Thus, even at the peak of their creative work, their very best games do not offer a sharp contrast to the other games in their game collections.

Nezhmetdinov was a player of inspiration. Such masters cannot have, and don't have, an even graph of first-rate games. A chronological graph of Nezh's games looks rather like a mountain range in which alongside with the highest peaks of his creative achievementshis eight thousand meter high mountainsthere are quite a lot of modest hillocks and separate rocks. Therefore, I divided select samples of Nezhmetdinov's creative work into several approximately equal sized groups.

In the first group I included genuine masterpieces. I am not afraid to call them masterpieces, as any of the chess greats might envy these games.

In the second group I put games which are saturated with big fights. They are distinguished by the high quality of play

from both combatants, though not devoid of mistakes.

The remaining games and fragments are divided among: attack, defense and counterattack, strategy, the opening, the endgame, and "small raisins."

Alex Pishkin Syktyvkar, 1999

Lasker and Petrosian were outstanding sportsmen, and from the present- Karpov. Steinitz, Euwe, and Botvinnik were distinguished by their scientific approach.

Alekhine and Tal can be called brilliant high priests of chess art.

It goes without saying that these champions were blessed by additional chess qualities as well, otherwise the list of champions would be different.

There are masters in whom certain chess qualities are developed to such a phenomenal extent that few of the recognised geniuses of chess can challenge them.

Are there many among the greatest who can compete in the theory of the endgame with Yuri Averbakh, Nikolai Grigoriev or Andre Cheron? Perhaps, only Smyslov and Rubinstein.

Are there many among the greatest who might surpass in the field of analysis Isaac Boleslavsky, Igor Zaitsev or Mark Dvoretsky?

But chess theory and analysis are still the applied side of chess. They are certainly necessary for a chessplayer, no less than the mastery of versification is necessary for a poet, and solfeggio, for a musician. What we value most of all in the poet and musician is the gift of creativity, that intangible, ephemeral thing which is called "a God's spark."

Among those who were endowed with "the God spark," and created many unforgettable masterpieces (though they never became world champions) were: Chigorin, Reti, Bronstein, Larsen, Ljubojevich ... To this list we should undoubtedly add Spielmann, Simagin, Tolush, Kupreichik and especially Nezhmetdinov.

The name of Rashid Gibyatovich Nezhmetdinov is not as well known to the western lover of chess. Indeed he is not included among "the greatest" of the chess world. He wasn't a grandmaster, though in the former Soviet Union one can count about two hundred owners of this title.

He wasn't famous in the international arena, simply because he had few chances to play outside of his own country.

Still, if you ask any chess master, no not even that, if you ask any man who likes art in chess and has become acquainted with the creative heritage of the chess masters of the past, he will surely say, "Ah, he is that master who regularly defeated Tal and who attacked so beautifully!" And that is true.

Despite his lack of the grandmaster title, Rashid Nezhmetdinov was a unique personality in the chess world.

In the USSR and, quite possibly, in the whole world, he was the only "master squared," that is, he was a chess master and a checkers master at the same time. Once Mikhail Tal jokingly called chess "algebra" and checkers "arithmetic." He hinted at a certain second-rate quality of a checkers game in comparision with a chess game, a game which many consider the "royal game." After Nezhmetdinov had finally given up checkers, he noted one time that all checkers contests can be reduced to Rook endgames. On the other hand, checkers players have often commented on the depth of calculations of variations in their favorite game, and especially its oriental varieties, like the Japanese "Go," as surpassing chess. We won't argue about this; these arguments increase the significance of Nezhmetdinov's double mastery of both games.

His talent fully blossomed and revealed itself when he was no longer young. He was 37 when he received the title of chess master. At that age, and even at a younger age, many famous chess masters disappeared from the scene (remember Fischer, Morphy, Pillsbury, Mecking... ?).

Nezhmetdinov gained his best results after 40. He made his debut in the USSR chess championship at 41, and the last time he became the Russian champion was at the age of 45. The last time he played in the finals of the all-Union championship was when he was almost 55!

In chess history you will seldom find similar cases of a chess player going on the "big stage" at such an "elderly" age. Some might remember Georg Salwe, the Russian champion of 1905, who also became a master after the age of 40. Contemporary chess practice shows that chess champions "are younger and younger," and that a chess player reaches his peak by the age of 25-30, and after 35, his sporting form slowly decreases. At that age, the ability to accurately calculate variations lessens. The ability to endure many hours of intensive mental exercise also declines, something which a chess master seriously needs. If this is true, and we cannot doubt the truthfulness of the conclusions of specialists, then how can we account for the phenomenal chess of Nezhmetdinov? This is even more remarkable if we take into consideration that his style of playing chess was primarily based on the increase of tension on the chessboard and the extremely intensive calculation of variations.

It is impossible to explain this, just as it is impossible to answer the question "How can one become a genius?"

Rashid Nezhmetdinov holds an unequaled record: he was chess champion of Russia five times. All in all, he played in the finals of the Russian championships 16 times.

Besides those five first places, another five times he was among the prize-

winners. Here also should be added a silver medal in one, the checkers championship. His closest rival among Russian chess champions is the great Chigorin, who won three championships at the beginning of the century.

His chess talent was unique. Lev Polugaevsky called him "the greatest master of the initiative."

M. Tal says: "His games reveal the beauty of chess and make you love in chess not so much the points and high placings, but the wonderful harmony and elegance of this particular world." Tal was a good friend and admirer of Nezhmetdinov's creative activity. In the preface to Nezhmetdinov's book Selected Games he wrote: "In Nezhmetdinov, more than in anybody else, you can see the difference between his creative and sporting achievements."

When a game was dry and there was much maneuvering, he got bored and sometimes played negligently. As a result, he lost more often than was expected. There were tournaments in which he never experienced a feeling of inspiration and creative enthusiasm. He didn't win laurels in those events.

On the other hand, when he managed to achieve a position that aroused the desire to create, when he succeeded in luring his opponent onto the slippery ice of combinational complications, when he obtained the initiative, then he was fearsome and irrepressible. It didn't matter then who was facing him across the board.

Rashid Nezhmetdinov's talent resembles a tree that, by some miracle, has grown on a bare cliff. He had a difficult childhood and was a youth of hunger. During his best years for chess he was in the army, and then came the

war. He gained access to serious chess competitions only when he was 35. It was much later when young talents in the Soviet Union could achieve wonderful conditions for growth and blossoming. They had experienced teachers in the Pioneer palaces, regular training meetings during school vacations, Chess Informants, and computers.

Rashid had no dreams of anything like that. Practically speaking, he alone created the brilliant chess master Nezhmetdinov. This might explain why Nezhmetdinov was not only a master, but also a brilliant coach who trained many masters and gave many young people their access to chess.

I hope this book will broaden the circle of admirers for the creative abilities of this wonderful chess player and perhaps arouse in some ambitious young man an aspiration to achieve something in the cruel and beautiful world of chess. Perhaps, another Super Nezh.

Personal Thoughts for the Westerner

I have never been Rashid Nezhmetdinov's pupil or friend. I met him only twice at team championships, but not at the chessboard.

In the 50s when I was making my first steps in chess, Nezhmetdinov's games appeared quite often on the pages of chess magazines. It so happened that it was through his creative play that I began to comprehend the beauty and depth of chess. Since that time I have always remained an unfailing admirer of his wonderful talent.

Unlike many other great Soviet masters, Nezhmetdinov enjoyed the respect of his contemporaries, and many of his games have become known to thousands of chess lovers; some very famous grandmasters cannot boast that. During his lifetime he had a book published about his life in chess (Kazan, 1960). The book was published by the provincial publishing house and the circulation was small. Unfortunately, not all of his best games were included. As for the second edition of that book, which was considerably expanded, Nezhmetdinov never saw it for he had passed away. It was republished in 1978, and this printing was larger, 50,000 copies.

Later J. Damsky authored an excellent book in 1987 to commemorate Nezhmetdinov's 75th birthday. Rashid Nezhmetdinov was published in an edition of 100,000 copies where Nezh is presented not only as a bright chess master, but also as a self-made man who devoted his life to chess, enduring many difficulties along the way.

Before I decided to write one more book about Rashid Nezhmetdinov, I studied thoroughly all that had been published, and primarily his games and commentaries on them. Nezhmetdinov's own notes are characterized by a laconic, terse style, and concrete analysis. My task was to remove some analytical inaccuracies and some very rare mistakes, as well as to refresh his opening theories.

Damsky's commentaries on some games are also good, especially if he himself witnessed those games or saw them demonstrated by Rashid. Unfortunately, Damsky's commentaries on some games are too curt and fail to fully reveal the depth of their contents. There are some analytical mistakes as well in Damsky's book. Some of Nezhmetdinov's brilliant games didn't get into Damsky's book or were only given as fragments.

In the end I came to the conclusion that it would be necessary to reselect

the games and to comment on them all over again.

I tried to use Nezhmetdinov's original analyses on those parts of the games that required detailed analysis. I also used his brilliant evaluations of positions which disclosed the real situation with utmost clarity and in few words. In these cases Nezhmetdinov's notes were quoted.

The selection of games has been changed according to their composition, as well as order of their arrangement. I have rejected the common method of chronological order in arranging the games. This approach to chess art is a good one for those great men of the chess world whose creative work is many-sided, and whose mastery is universal. The average level of games of those type of masters is high. Thus, even at the peak of their creative work, their very best games do not offer a sharp contrast to the other games in their game collections.

Nezhmetdinov was a player of inspiration. Such masters cannot have, and don't have, an even graph of first-rate games. A chronological graph of Nezh's games looks rather like a mountain range in which alongside with the highest peaks of his creative achievementshis eight thousand meter high mountainsthere are quite a lot of modest hillocks and separate rocks. Therefore, I divided select samples of Nezhmetdinov's creative work into several approximately equal sized groups.

In the first group I included genuine masterpieces. I am not afraid to call them masterpieces, as any of the chess greats might envy these games.

In the second group I put games which are saturated with big fights. They are distinguished by the high quality of play

from both combatants, though not devoid of mistakes.

The remaining games and fragments are divided among: attack, defense and counterattack, strategy, the opening, the endgame, and "small raisins."

Alex Pishkin Syktyvkar, 1999

Zugegeben: Der Name Rashid Nezhmetdinov war mir bis zum Eintreffen des Buches "Super Nezh" allenfalls von einem schönen Sieg gegen Tal (Moskau 1959) und natürlich durch seine sensationelle Partie gegen Polugaevsky (Sochi 1958) bekannt. Die Art und Weise, wie er beide Partien für sich entschied, macht aber sehr neugierig.

Viel Interessantes bietet bereits die Biographie Nezhmetdinovs. Er war bereits 37 Jahre alt, als er sich 1950 den Meistertitel erkämpfte, und obwohl sich die Liste der von ihm in den folgenden Jahren Besiegten wie ein Who-is-who des sowjetischen Schachs liest (z.B. Boleslavsky, Bronstein, Flohr, Geller, Mikenas, Spassky, Suetin und dreimal Tal), blieb ihm dennoch der Titel eines Großmeisters versagt.

Folglich erhielt er selten Gelegenheit, an ausländischen Turnieren teilzunehmen, zumindest in der Sowjetunion sicherte ihm seine attraktive Spielweise, die von kompromisslosem Streben nach Initiative, großer Phantasie und kühnen Kombinationen geprägt war, jedoch eine große Popularität.

Natürlich hatte sein Spiel auch seine Schattenseiten, die 100 in diesem Buch enthaltenen Partien zeigen ihn jedoch auf der Höhe seines Könnens.

Autor Alex Pishkin, Internationaler Meister im Fernschach, hat sie nach Art der Partien in verschiedene Kapitel unterteilt und ausführlich kommentiert, bei den meisten Partien finden sich auch noch einige Kommentare von Nezhmetdinov.

Im Anhang sind noch einige Turniertabellen, ein Verzeichnis seiner Gegner, ein Eröffnungsindex sowie eine Übersicht seiner Turnier- und Wettkampfergebnisse enthalten, letzteres übrigens auch über Nezhmetdinovs Aktivitäten im Damespiel, in dem er es auch zu großer Meisterschaft brachte.

Fazit: Alle Freunde von phantasievollem und wagemutigem Angriffsschach werden an diesem Buch große Freude haben, zumal auch der Druck und die Kommentierung sehr gut sind.

Viel Interessantes bietet bereits die Biographie Nezhmetdinovs. Er war bereits 37 Jahre alt, als er sich 1950 den Meistertitel erkämpfte, und obwohl sich die Liste der von ihm in den folgenden Jahren Besiegten wie ein Who-is-who des sowjetischen Schachs liest (z.B. Boleslavsky, Bronstein, Flohr, Geller, Mikenas, Spassky, Suetin und dreimal Tal), blieb ihm dennoch der Titel eines Großmeisters versagt.

Folglich erhielt er selten Gelegenheit, an ausländischen Turnieren teilzunehmen, zumindest in der Sowjetunion sicherte ihm seine attraktive Spielweise, die von kompromisslosem Streben nach Initiative, großer Phantasie und kühnen Kombinationen geprägt war, jedoch eine große Popularität.

Natürlich hatte sein Spiel auch seine Schattenseiten, die 100 in diesem Buch enthaltenen Partien zeigen ihn jedoch auf der Höhe seines Könnens.

Autor Alex Pishkin, Internationaler Meister im Fernschach, hat sie nach Art der Partien in verschiedene Kapitel unterteilt und ausführlich kommentiert, bei den meisten Partien finden sich auch noch einige Kommentare von Nezhmetdinov.

Im Anhang sind noch einige Turniertabellen, ein Verzeichnis seiner Gegner, ein Eröffnungsindex sowie eine Übersicht seiner Turnier- und Wettkampfergebnisse enthalten, letzteres übrigens auch über Nezhmetdinovs Aktivitäten im Damespiel, in dem er es auch zu großer Meisterschaft brachte.

Fazit: Alle Freunde von phantasievollem und wagemutigem Angriffsschach werden an diesem Buch große Freude haben, zumal auch der Druck und die Kommentierung sehr gut sind.

Mehr von Thinkers' Press

-

Journal of a Chess Original15,00 €

Journal of a Chess Original15,00 €